It is the Classical Language Exam Time of the Year!

by Amy Barr, The Lukeion Project

This week’s blog is going to be a bit more specific to TheLukeion Project as we discuss the National Greek Exam (March 2, 2020) and The

National Latin Exam (March 9, 2020). I’ll answer the most frequently asked questions

about why we participate in these exams and offer some last-minute encouragement as you prepare for these competitions.

Why does The Lukeion Project participate in the NGE and NLE each year?

There are a zillion different approaches, curricula, and

programs that promise students a chance to study Latin and Classical Greek.

Sadly, some of these approaches offer no more than vague language familiarity,

even after several years of “hard work.” Others—especially The Lukeion Project—make language

mastery the goal. How can we make this claim without some standardized exam results

to back us up? More importantly, how can you –the student—claim to have attained excellence without some standardized test results to

back you up? Participating in the NLE/NGE is a great opportunity to compare your efforts to other students worldwide.

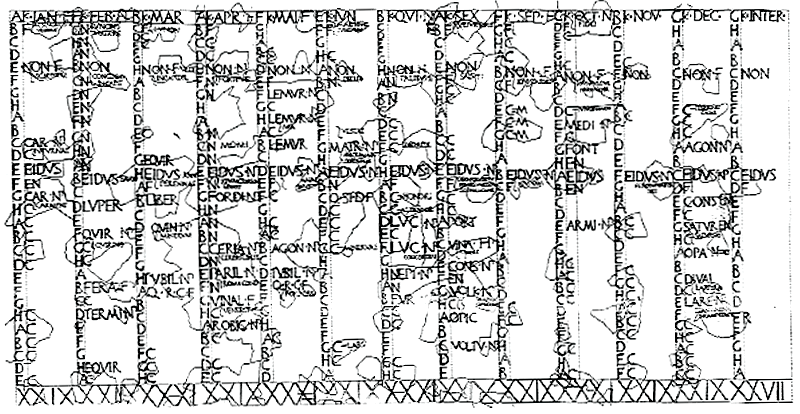

“The National Greek Examination in 2019 enrolled 1774

students from 173 high schools, colleges, and universities in the US and around

the world.” There are seven levels: Introduction to Greek, Beginning Attic,

Intermediate Attic, Homeric Odyssey, Homeric Iliad, Prose, and Tragedy. The

exam is offered by the American Classical League.

Roughly 140,000 students take the NLE. “The National LatinExam (NLE) is a test given annually to Latin students across the United States

and around the world. The NLE is not meant to be a competition but rather an

opportunity for students to receive reinforcement and recognition for their

accomplishments in the classroom. Depending upon their score, students may earn

certificates, medals, and may even qualify for scholarships.” The exam is

sponsored by the American Classical League and the National Junior Classical

League and is offered to students on seven levels.

Neither the NGE nor the NLE exams are based on any specific

textbook series so students will be put to the test in a fair comparison across

the board. Roughly half of the students who participate worldwide will earn honors at varying levels.

On average, 95% of Lukeion Latin students and 90% of Lukeion Greek students earn honors each year. For the NLE, Lukeion students typically earn in the ballpark

of 3% of all perfect papers scored each year worldwide.

Shouldn’t I “wait until I’m better” at the languages before taking the test for the first time?

Both the NGE and NLE exams come in 7 forms and are meant to be taken annually

for every level completed by the student. Students gain valuable

experience by taking exams yearly and they might also be awarded special book

awards (and even a shot at scholarships) if they earn gold medals for three

successive years. Around a dozen Lukeion advanced students (NLE III –

NLE VI) will be awarded prestigious book awards for three (or more) years of

success annually. While scholarships are very limited, students are only offered the chance

to apply for them after completing the NLE III level. So, take the exam that corresponds to your level from the start (we do not offer the Intro level for our students)

Do I get credit in my language class? If not, why bother to study?

Much satisfaction can be realized when one prepares well for a

challenge and when one is recognized for the attainment of mastery of that challenge. This fact has been true about human beings for as long as we have records regarding the fastest, smartest, and bravest. There’s

a tremendous feeling of success shared by those who compete and do well in

sports, debate, performance, cooking, painting, or…Greek and Latin! Working

hard is its own reward but getting a bit of extra recognition for that hard

work – at the international level – is a nice boost to one’s confidence.

Taking any exam makes me nervous so why voluntarily take something like the NLE or NGE?

Many of us are naturally exam adverse. Reasons can include test-anxiety,

fears of failure, or maybe a little laziness, truth be told. Academic tests are inevitable unless

you plan to quit your formal education quite young. The only thing that makes all those inevitable quizzes,

tests, and exams more endurable is practice and experience. The NLE and NGE offer

the added benefit of (a) not causing any permanent damage to your transcript if things go

badly, and (b) the potential of much laud and honor if things go well. In other words, do your best but there's nothing to lose.

So, why voluntarily put yourself through extra study effort over the next few days leading up to your NGE and NLE dates? For now, you’ll

improve your language mastery, which will benefit your course grade. In the

future, you’ll demonstrate your language mastery, which will strengthen your future

transcripts. In the long run, you’ll attain language mastery, which will

strengthen every part of your thinking, writing, and speaking henceforth!