Time Meanders More than You Know

By Amy Barr, The Lukeion ProjectHistory timelines can be fine teaching tools. They provide a crisp visual to help us understand where goalposts stand as we look backward. Goalposts can help us see cause and effect, such as when the printing press lead to a surge in literacy; automobiles enticed people from cramped cities into suburbia; soap extended lifespans and freshened the air. But history really isn’t simple, and it is never a straight path. Connecting dots to make a few straight-line history lessons tends to leave out lots of dots!

Relationships between world events are less like timelines and more like ripples in a pond or crisscrossed spider webs. To appreciate history, you must meander a labyrinth, not walk a line.

Specific dates of even major historical events are seldom known with certainty as we travel further back in time. Humans have recently all gotten together to rely on a neat 12-month calendar and a new year each January 1st. They mostly do so now only because our computers and airports require this common time language. Some nations enjoy more than one date-keeping system to accommodate technology and tradition at the same time.

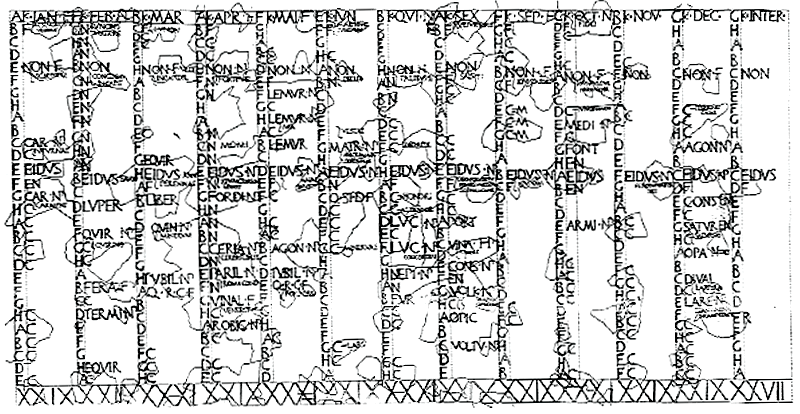

Before computers helped standardize date keeping across the globe, humans recorded events by calculating the time since the last Olympiad, the years since the start of a king’s rule, the decades since the last eclipse, or the centuries since a city was founded. Serious historians don’t just flip to a single commonly accepted timeline when they want to talk about when things happened. A good bit more math and mystery must be solved to build goalposts on the ancient timeline.

How can one mark a permanent “X” on the timeline of history? Consider the founding of Rome. Textbooks tell us Remus lost the bid to name the city to his twin, Romulus, in 753 BC. The actual date of this fraternal squabble was debated for centuries by the Romans themselves. Over 700 years after the event some Romans favored the theory it all took place on April 21st soon before an eclipse calculated 438 years after the fall of Troy (Velleius Paterculus, 8). An equally compelling theory put Rome’s founding in 747 BC, dating it to the 8th Olympiad.

After the monarchy, the Romans themselves mostly kept track of time by the name of the two consuls in charge each year. Romans started counting years after Rome was founded using the AUC system (ab urbe condita). In AD 525 Dionysius Exiguus attempted to calculate the year of Christ’s birth and started numbering the years of history from that point starting with AD 1 (anno domini). All years prior to that date were later termed in English “BC” for “Before Christ.” This way of numbering years did not catch on broadly until after AD 800. Historical scholars working with all primary texts for events prior to AD 800 need to be chronologically savvy about the various dating systems in play.

Knowing what year it was could be problematic for an ancient person. Knowing what day it was could be impossible. Trial and error taught people some systems were more reliable than others. The moon was an easy calendar guide since it was visible everywhere, and lunar cycles divided the year into months of 29 or 30 days. Lunar months don’t add up to 365 ¼ days a year. Every few decades the days and months drifted out of season. Harvest holidays would show up in icy winter and spring holidays were celebrated in sweaty summer. In Rome, politicians were asked to toss in an extra month to even things out. It was hard to write to a friend in Thrace or Egypt to meet in Athens or Rome on a definite day. Everyone kept track of dates a bit differently. Appointments always allowed for plenty of flexibility.

On February 24 in AD 1582, a large part of the planet got on-board with the solar calendar system we use today. All Catholic countries of Europe agreed to keep time the same way when an edict was issued by Pope Gregory XIII. His reason for strictly regulating the calendar was so all Christians could celebrate Easter on the same day. This idea was first suggested by the church fathers at the Council of Nicaea in AD 325 but the idea got stuck in committee for a very (very) long time.

This Gregorian calendar of AD 1582 fixed flaws in the older system set up in 45 BC by Roman statesman Julius Caesar. That wily old politician won the powerful office Pontifex Maximus early in his career. Among other perks, his job as Pontifex required him to declare an intercalary month between February and March as needed whenever the months of the year started to get off track. Ever the consummate politician, he took the best advantage of the situation. He was allowed to make some years longer to extend the political terms of allies, or make them shorter is an adversary was in office.

With a hectic schedule of conquering Gaul, fighting Pompey, and touring Egypt meant the Roman calendar was neglected by Caesar too long. He finally found a moment to fix time in 46 BC. In addition to the traditional spare month between February and March, he added another 67 days between November and December. That year seemed to go on endlessly, but Caesar’s new Julian calendar was a hit. It followed the solar year closely and the Romans enjoyed the luxury of knowing when summer started, when to make plans for Saturnalia, and when to plant a garden.

“March,” “April,” “May,” “June,” plus “September” (7), “October” (8), “November” (9) and “December” (10) were named by Romulus in his original 10-month calendar. The next king added January and February to the start of the year. Months named “seven” through “ten” became months nine through twelve evermore. The Roman month Quintilis would be later be renamed “July” but only after Julius was slain. The month Sextilis became “August” to honor Caesar’s heir, the first Roman emperor Augustus. Other emperors tried to rename months but failed (thankfully). Emperor Commodus, for example, energetically named all the months after himself. The Romans quickly flushed those names down the drain once he died.

Relationships between people, places and events can make history a wonderful web of cause and effect. Like ripples in a pond during a rainstorm, events combine and overlap with surprising results. Each nation has used different ways to mark time. As you study history this year, make marking time part of the puzzle to be solved.

No comments:

Post a Comment