Most Beautiful, Weirdest, and Most Informative

[Note: this was originally intended to be part of a series of weekly notes sent to all current Lukeion students but we decided this was certainly blog-worthy!]

By now you know that your Lukeion Project Instructors love many things about the ancient and not-so-ancient world, but do you really know their favorites? This week I asked our instructors to tell me their favorites in three categories:

- Most Beautiful

- Weirdest

- Most Informative.

MOST BEAUTIFUL:

Mrs. Barr: The Blue Cameo Vase from Pompeii. Why? Because that specific color of blue is my favorite but (to sound more scholarly) also this: How the Roman artists made this vase is still largely a mystery. I love when ancient skills are better than what the modern mind can conceive!

Mr. Barr: After anguishing over my answer, I've decided to go with the Temple of Athena Pronaia at Delphi because of its beauty within the context of its environment.

(Although the Nike of Samothrace was a very close second!

Mrs. Baty: The play “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” because it’s just so much fun!

Dr. Fisher: The bee pendant from Malia, Crete. Why: it's gold and who doesn't like shiny things? Plus, the technique including granulation on such a small scale is very impressive, especially for c. 1800 B.C.!

Dr. Fisher: The bee pendant from Malia, Crete. Why: it's gold and who doesn't like shiny things? Plus, the technique including granulation on such a small scale is very impressive, especially for c. 1800 B.C.!

(Although I’m also REALLY partial to the Apollo Kylix from Delphi, Greece c. 480-470 B.C.)

Dr. Haggard: Marcus Aurelius. What is most beautiful is that he was a man of privilege as one born into nobility and nurtured by emperors, yet he learned from a Stoic slave to be humble and more concerned for others than himself.

The WEIRDEST:

Mrs. Barr: Mine isn't a specific artifact, but a study was done on human remains from Herculaneum and nearby villas. Residue inside the cranial cavities reveals that the poor victims of the pyroclastic flow from Vesuvius were not only instantly vaporized but their bones (which were not vaporized) actually floated midair for a fraction of a second.

Mr. Barr: I'm going to go with the mosaic of the skeleton carrying jugs from the House of the Faun in Pompeii. Even if the skeleton were able to get water or wine or whatever if it tried to drink, where would the liquid go? (The Memento Mori mosaic with the monkey skull was a close second.

Dr. Fisher: The bronze liver of Piacenza. Seriously? Who builds models for reading sheep entrails? The Etruscans did, that’s who! And if sheep entrail reading wasn’t enough, it is inscribed in the Etruscan language which is largely untranslatable.

For some more info go here.

Dr. Haggard: Diogenes. When Alexander the Great offered him anything at all, Diogenes asked him to move out of the way since he was blocking the light. In a rich man’s home, Diogenes was asked to not spit on the floor so Diogenes spit in the man’s face claiming, “it was the only worthless thing in the room on which to spit.”

MOST INFORMATIVE:

Mrs. Barr: This was a very difficult category to answer so I'll have to say the remains of the scrolls at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum. This villa (which was packed full of perfectly preserved bronzes) is a dream come true! It is a preserved ancient library! Although it was first discovered in 1752, modern research is finally starting to pay off so we can read the hundreds of burned scrolls. There are high hopes that archaeologists will find hundreds more in the years to come.

Mr. Barr: The archaeological site of Akrotiri on Santorini because it is a time capsule of the Minoans.

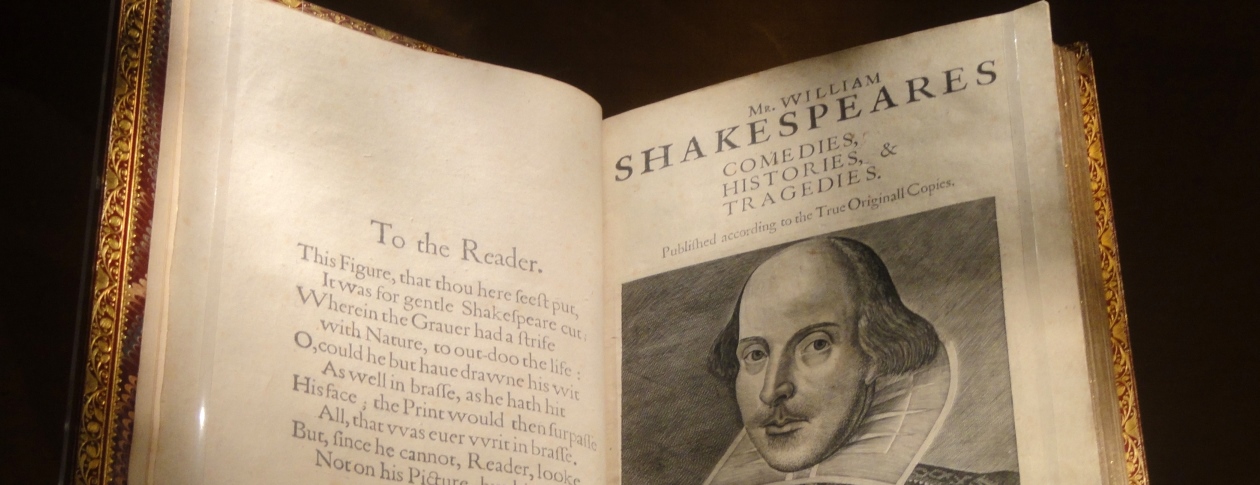

Mrs. Baty: The First Folio. Many of the plays that we love from Shakespeare wouldn't still be in existence if his friends hadn't decided to gather everything up after his death and get it published.

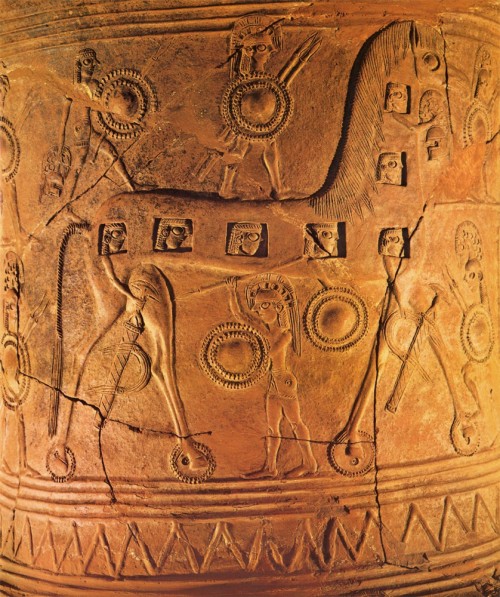

Dr. Fisher: I’m a big fan of the crossover of archaeology and literature, especially in the Archaic period when the Greeks first began writing their poetry down. Therefore, the Mykonos Vase c. 670 B.C. with its earliest depiction of the Trojan War gets my vote for most informative, as it helps us date the canonization of Homer’s epics.

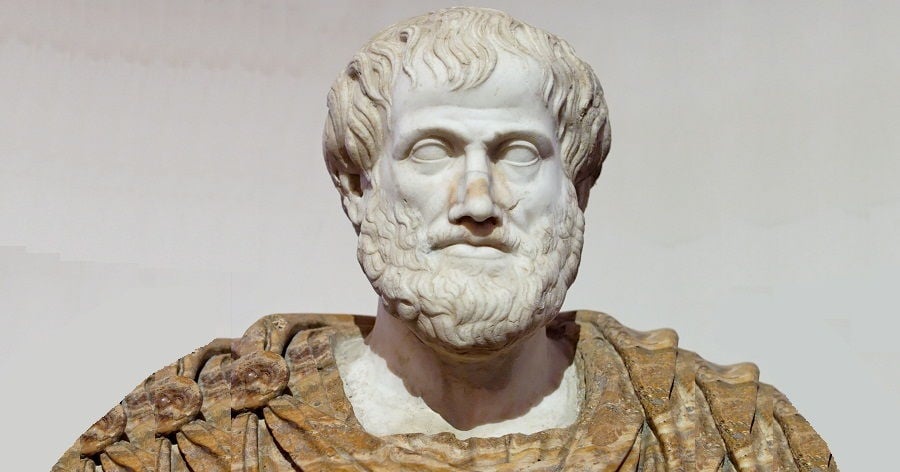

Dr. Haggard: Aristotle. As wiki says, “his philosophy has exerted a unique influence on almost every form of knowledge in the West and it continues to be central to the contemporary philosophical discussion.” And I am in full agreement. He formalized logic and reason. Had the east had a student of Eastern Philosophy such as he, Confucianism and Taoism might not be the fortune cookie mysticism people take them for today.