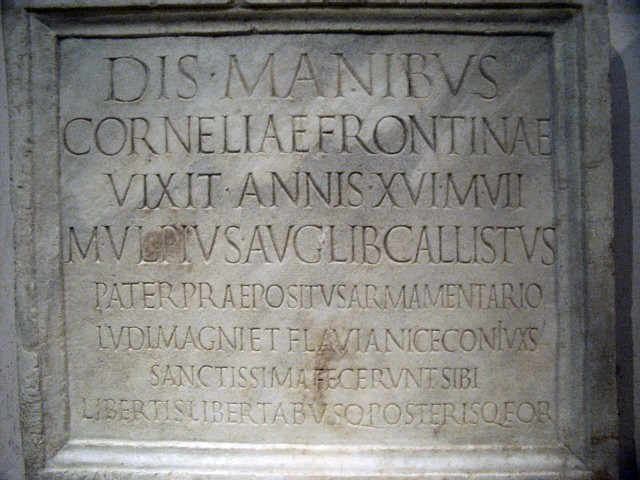

Ave atque vale dis manibus

By Amy E. Barr

There’s a crisp feel in the air, your neighbors might be decorating their yard in zombie themes, and most people are planning on at least a slight uptick in sweet treats soon. Now is the right time to serve up a seasonally appropriate topic of Classical ghosts. While Classical cultures generally enjoyed their occasional specters, it was the Romans who adored their ghost stories.

Now to clarify, I’m not talking about current Roman hauntings like this story from Hadrian’s Wall or this group of Roman soldiers sighted in 1953, York. The Romans themselves enjoyed ghosts of all sorts very much. They were also careful to tend their ghosts to keep them happy.

One of the best examples of ghosts with the most was the assortment from "the very helpful" di manes category that Vergil includes in the Aeneid. In book 1, we have Dido’s dead husband telling her to grab the gold and clear out quickly to found the city Carthage before her creepy brother could catch her. In book 2, we have a very grisly Hector telling Aeneas to wake up and leave Troy. Soon after that Aeneas’ (recently dead) wife, Creusa tells him to get a move on, thank you very much. Not satisfied with earthly specters, Vergil visits his hero to the di inferi and the fabulously eerie underworld (book 6), where Aeneas has an awkward conversation with recently dead Dido. Fortunately, Aeneas has a more fruitful exchange with dear-old-dead-dad who encourages him in fine Stoic fashion to follow his fates. Aeneas also runs into his freshly deceased helmsman who is in need of a nice burial.

That’s a pretty good body count! Clearly, Vergil considered ghosts to be the best way to advance a plot and hold a Roman audience. The Romans had certain rules about the type of dead person who might appear in dreams. Only friends and loved ones could pay a visit while you snoozed. When they did, they usually had dependable advice which should be immediately believed. Thus, Vergil describes these sorts of ghosts as extremely reliable sources of information.

Historian Pliny the Younger wrote this chilling ghost story, complete with rattling chains and a haunted house. This one serves as a good example of how properly level-headed Roman philosophers can help even an old dead guy, all while getting a great bargain on a house. My Latinists might want to try to translate this story from the Latin by visiting here.

February rather than October was the normal month for Romans to attend family graves which were all placed on the roads outside of town limits. If you ever visit Pompeii, be sure to take the path out of town to the Villa of the Mysteries to get a good look at the rows of Roman grades still in place there.